PART 2

The Present

The port strike is an important precedent for understanding the “Umbrella Movement,” since today’s occupiers will doubtlessly be faced with the same dilemma. Just like the strikers, they risk becoming deadlocked between appealing to civil society and deepening their economic obstruction. Already, internal divides within the movement make this apparent. Most of the younger protestors have completely rejected the leadership of “Occupy Central with Love and Peace” group, lambasting Chan Kin-man when he claimed that the blockades would end if Chief Executive CY Leung stepped down. Meanwhile, these same young people have parroted popular language about democracy, universal suffrage and non-violence—demanding that no property be harmed and that people not fight back even if the police attack.

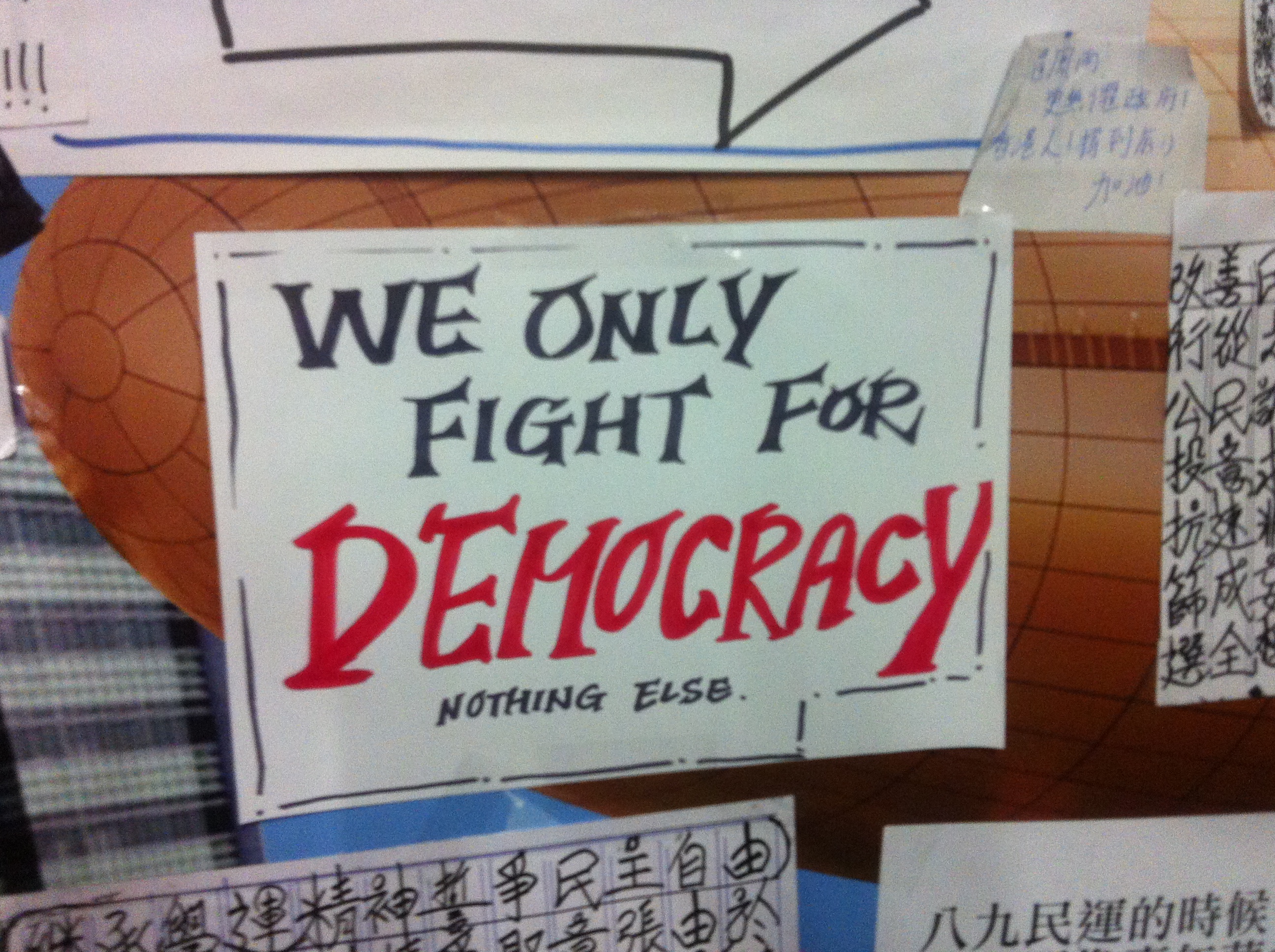

A poster encouraging people to use non-violence, and to fight only for democracy (but not literally)

This servile spirit of “politeness” risks stranding the protestors in a dead zone. In this dead zone, they’ll find themselves incapable of escalating the economic disruption that gives power to the movement—since many see even damaging private property as uncivil—and this inaction will make it easy enough for the government to starve out or appease the protestors with more minor concessions, such as the firing of the Chief Executive. Many, though aware of this conundrum, are equally fearful that (rumor has it) gangster provocateurs[v] might escalate the situation on orders from Beijing, creating a convenient excuse for a military occupation of the island.

An interesting contradiction arises here. The latent nationalism of the protests makes it so that the police, as “Hong Kong people,” are seen as allies and potentially future participants, while the intervention of the military—even if it used all the same tactics as the police—would be universally rejected. This is because the military units themselves would be composed of mainlanders under the direct order of Beijing, rather than the secondary control of Beijing’s Hong Kong politicians. For the protestors, this does not represent any sort of logical contradiction. Many firmly hold to the position that it is counterproductive to fight police or resist arrest, then, in the next sentence, argue that people would be fully justified in using violent tactics to resist the military.

A populist perspective prevents the recognition of any antagonism internal to “the people,” transposing the source of all conflict outward onto external groups, whether defined by race, national origin or simply immigration status. When such populism is predominant, riots, property destruction and even “impoliteness” on the part of protestors will be invariably written off as the work of “outsiders”—in this case, mainland Chinese—at least until they generalize. But strikes have a much greater propensity to break such a populist logic, since they immediately make visible antagonisms internal to the given society.

Abandoned public buses plastered with protestors’ messages. Note the characters, top center, referencing the “Democracy Wall” movement in mainland China from 1979-1981.

Another barricade, this time with two cars parked in front to ensure that the police cannot easily break through. One car has had its tires removed in order to prevent it from being pushed away.

The current movement has only a few paths forward, and many routes to defeat. The tactical stagnation of the protests could allow the government to simply wait them out, as the protestors’ own inaction delegitimizes them in the eyes of more casual participants. There are already complaints from people who have newly joined the protests that the entire movement seems to be simply drifting, with no real force leading it forward. At best, the revolt may fail by becoming a “social movement”—a sterile spectacle put on for civil society, where future NGO leaders and politicians gestate before being unleashed upon the poor. At worst, the people of Hong Kong might actually get the popular vote, in which case they’d be allowed an enormous amount of participation in a system over which they have no control and in which all the same problems of inflation, inequality and immiseration would continue unabated.[vi]

In this situation, however, there is also the risk that defeat might come in the form of a resurgent rightwing. If the far-right is capable of becoming the force that can torque the protests out of their stagnation, then the movement as a whole will slide farther down the path of nationalism. In the current “era of riots,” the right-wing tends to be capable of magnetizing people to itself regardless of whether the majority of people agree or disagree with the racist politics of groups like Civic Passion—which went normcore early on in the movement, abandoning its public presence in favor of an “undercover” agitation, spreading flyers and speeches attacking the inaction of the “leftist pricks”[vii] in charge, and only more recently has become a visible presence, their yellow-shirted members defending the barricades in Mong Kok (barricades built by anarchists, no less) against attempts by “blue ribbon” opponents (mostly older anti-Occupy protestors) to dismantle them.

This situation bears a miserable similarity to the experience of Ukraine, with the far-right acting as hatchet men for an alliance of more West-leaning capitalists.

A small group of Civic Passion members defending a barricade from being dismantled by other members of the occupation. This role has not always been played by the right-wing, but acts like this reinforce their public presence. Note that their yellow shirts say, in English: “proletariat,” consistent with the general usurpation of leftist terminology by far right or “third positionist” groups.

![Translation: Don't trust leftist pricks Be vigilant [lest they ask us] to disperse Remember that we are [doing] civil disobedience, not having a Party!!! What we want is TRUE UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE!!! No karaoke No group photos We still haven't won No leaders No small-group discussion](http://www.ultra-com.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/1001MK_2.jpg)

Translation: Don’t trust leftist pricks

Be vigilant [lest they ask us] to disperse

Remember that we are [doing] civil disobedience, not having a Party!!!

What we want is TRUE UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE!!!

No karaoke

No group photos

We still haven’t won

No leaders

No small-group discussion [this refers to "discussion groups" organized by liberals]

Be vigilant [lest they ask us] to disperse

Remember that we are [doing] civil disobedience, not having a Party!!!

What we want is TRUE UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE!!!

No karaoke

No group photos

We still haven’t won

No leaders

No small-group discussion [this refers to "discussion groups" organized by liberals]

It’s not about “Democracy”

But defeat is by no means inevitable here. Young people in Hong Kong, like pretty much anywhere these days, are recognizing that their future has been looted and are attempting, through whatever means they have available, to both reach some understanding of how they have come to be in this position and how they might fight back. In Hong Kong, China is very much “the future,” as the small city-state is integrated more and more into its massive mainland neighbor.[viii] This means that the sense of a doomed future among youth translates into the intuition that China is also the origin of that approaching doom.

There are plenty of young protestors who are frustrated with the inactivity of the movement, but feel isolated and incapable of pushing anything forward themselves. This is especially true at night, when more of the angry and dedicated young people tend to come out, but there are currently no means whereby these protestors are able to make contact with one another and coordinate their activity. More importantly, even these protestors tend to translate their discontent into the language of “democracy” and “universal suffrage,” and they fail to look across the border to find allies among the factory workers of the Pearl River Delta.

But despite the fact that the pan-democrats’ terminology is the lingua franca of the movement, it’s clear that the movement itself is, for many people, hardly about liberal “democracy.” In fact, most discussions of what protestors actually want quickly jump into entirely different terrain. When asked what their goals are, many will respond with the parroted list of demands—this is incredibly consistent across social strata and different age groups. But when pressed about why they want these things, most protestors then immediately jump to economic, rather than purely political, problems.

People bemoan skyrocketing rents, the inhuman levels of inequality, inflation in the price of food and public transport, and the governments’ tendency to simply ignore the vast swaths of people sitting at the bottom of society.

One speaker at an open mic made the common—if simply wrong—argument: “Why is Hong Kong just a couple of rich people and so many poor people?! Because we have no democracy!” Many claim—with abysmally poor awareness of how liberal democracies actually function in places like Greece or the United States—that once they are able to “choose” their own leaders these leaders will be able to fix widespread problems of inflation, poverty and financial speculation. Democracy has thereby come to designate less the practical application of a popular voting system and more a sort of elusive panacea, capable of somehow curing all social ills.

An older man, originally from Hong Kong, he left before the handover. In town visiting family, he is seen here having picture taken in front of the barricades. Visible at his right is the word “Democracy.”

But both the populist and democratic illusions of the movement are capable of being destabilized. As the occupation spreads to broader segments of the population, new participants bring their own demands to the barricades. Some of the original liberal students, including the HKFS leadership, have become increasingly frustrated by this, and have been plastering up signage encouraging people to stick to demands of universal suffrage. Interviewees have expressed the fear that the movement will get “confused” and “watered down” by many of the new protestors, who have come out to protest against the police attacks on students more than they are protesting for electoral reform.

But it’s just as possible that the new demands may actually re-ignite the movement itself, pushing it beyond the domain of mundane electoral demands. Generally, when class strata far distant from those that initiated the movement begin joining in, it signals a sort of phase shift in what is going on and amplifies the movement’s power, rather than watering it down.

A poster requesting that people stay “on point” and that new protestors stop demanding things beyond electoral reform

One particularly volatile potential is the increasing involvement of workers. The relatively small Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions has called for a general strike and, on October 1st (China’s “National Day”), at least some workers began heading the call.[ix] Several of the port workers who were involved in the initial dock strike were also present early in the week, showing their support for the protestors, though also claiming that another port strike seemed “impossible.” But as the occupation in the streets continues to grow, particularly in areas with more residential housing such as Mong Kok, it becomes more and more likely that other workers may begin to join in.

The extension of the occupation into a general strike would have the added effect of inherently destabilizing both the exclusively political demands of the movement as well as questioning its populist presumptions. If the port workers were to initiate a second strike, for example, there would be no denying the role of Li Ka-shing and other Hong Kong capitalists in the plundering of workers’ everyday lives and the pillaging of young peoples’ future.

It would be simply impossible to defer this conflict out onto mainlanders. The class antagonism internal to Hong Kong would become increasingly undeniable, and the protests could be forced off their path-of-least-resistance and toward a future simultaneously more dangerous and hopeful.

The Typhoon

Tsim Sha Tsui is now occupied, but the rumor is that the right-wing has a strong presence. Barricades have been built outside the shopping mall and crowds huddle under umbrellas, debating the future of the movement under the looming shape of the cruise ship. The right-wing pretends that the cruise ship is just full of mainland capitalists, while the left-wing seems unable to speak. The girl singing Cantonese love songs and her boyfriend playing off-tune guitar are gone now, maybe building a barricade somewhere out of tourist kiosks and traffic signs. But the singing is not so much simply absent as it is transformed, extending now to the entire city in the shape of people’s hopes plastered onto emptied buses and rain-splattered government buildings.

The typhoon has come, and the waters are shaking so violently that it’s unclear how much longer the cruise ship can sit immobile above the city. Its wealthy denizens, mainland and otherwise, sit quiet and invisible behind the white walls and cordons of police. If the pier is occupied, will the port come next? Despite the miserable servility of Hong Kong politeness, the short-sighted demands and the bitter populism of the movement, it is at least clear that, after this, Hong Kong will not be the same. There is no longer the possibility of preserving the status quo—and this fact, if anything, ensures that there is a potential to the movement, even if it is defeated.

The typhoon is by nature a chaotic creature, and, after the island is flooded, it may seem to leave things even worse than they were before. But that chaos also holds a certain promise. The breaking of the status quo cuts a glimmer of possibility in a horizon that had appeared before as nothing but sheer doom. There is an opening. Maybe people begin to learn how to navigate toward it, despite the rain.

And, even if it keeps raining for years to come, people have umbrellas.

—an American ultra and some anonymous friends

[i] For a more detailed history of China’s economic opening and the role of East Asian capital in the late 20th century, see Giovanni Arrighi’s article, “China’s Market Economy in the Long Run,” in China and the Transformation of Global Capitalism, edited by Ho-fung Hung. John’s Hopkins University Press, 2009. p.22.

[ii] It has to be noted here that out-migration today is still far lower than out-migration in the early 1990s, when as many as 60,000 were leaving every year.

[iii] This information comes from interviews with several people in Hong Kong’s post-Occupy milieu who were present on the first few days of the strike and organized alongside workers throughout.

[iv] Much of the information in these last few sections comes from first-hand accounts by people we are in contact with on the ground, who have been conducting interviews and inquiring into the state of the different political factions involved. Some of the people we are in contact with were involved in the initial student strike. Others have only begun participating after the police crackdown. Because of the first-hand quality of the information, these sections will frequently provide information, including quotes from interviews, without a link or citation.

[v] In Hong Kong, many of the organized gangs are now “patriotic,” working with the Hong Kong government and serving the interests of Beijing. This is not universally true, however, and the rumors of Beijing-backed gangster provocateurs have run up against reports of Mong Kok gangs working with the protestors to build up the barricades.

[vi] There may well be something to the claim that a future Hong Kong democracy would create a political space where class antagonism could be galvanized in a way that ultimately goes well beyond the bounds of reformist politics—this is essentially the argument (as far as we can gather) of some groups like Left 21. Nonetheless, this is a disingenuous position, basically attempting to continue the delusion a little longer and defer the recognition of antagonism indefinitely. Usually deferring action to the “right time” is simply a method of rejecting action altogether.

[vii] Literally “左膠,” “left penises” in Cantonese, referring to the pan-democratic leadership more than the (largely invisible) leftist grouplets. 膠 is a word that literally means plastic but is also used to mean dick, due to the similarity between the sounds of 膠 and 鳩, a more common euphemism for penis (though it literally means turtledove). The insult of “leftist prick” has in the past day or two gained broad purchase in the movement, and can be heard repeated every major occupation in the city. Even leftists have begun using it as a good, short-hand insult for the pan-democrats. There’s nothing inherently bad in the use of the term—despite some soft-stomached leftists’ inevitable butthurt—the problem is more that it is the far right that has put itself in the position to coin and popularize slogans that are being picked up by the entirety of the movement. When these slogans (or aesthetics, or tactics, or whatever) generalize, it puts the right-wing in a de facto leadership position.

[viii] Since the 1997 Handover of the island from British Colonial Mandate to the Chinese government happened to occur at the same time as the Asian Financial Crisis, China is also irrationally associated with the era of economic stagnation that this crisis initiated for Hong Kong.

[ix] It’s ambiguous, however, whether claims of “10,000 striking workers” have any connection to reality, since National Day is also a national holiday on which many workers are not required to come to work in the first place. Many, given the holiday, simply came to the occupations instead, since they had the day off. By no means were these people “striking.”

SOURCE: http://www.ultra-com.org/project/black-versus-yellow/

No comments:

Post a Comment